Simulacra. The Ladies of the Court.

Through a work that places itself at the intersection of various arts – painting, photography, embroidery and stop motion animation – Maria Kotsou tackles the “images” of the Ladies of the Court.

“People abhorred and hated the diabolic instrument

that could create a second self,

thus replacing God,

but also removed their inner power

in order to give it to their diabolic simulacrum (the photograph).”

M.G. Meraklis, “On Photography”, Folklore issues, Athens 1989

Beyond the early Greek portraiture that begins to develop during the first post-revolutionary years, photography brings the privilege of faithfully depicting the face a step closer through the proliferation of daguerreotype process, the first commercial imaging technique, introduced in 1839 by the French painter Louis Daguerre.

As photography begins in Greece in the first half of the 19th century, it provokes feelings of witchcraft and mystery. The first daguerreotype portraits, as well as the first lessons in the daguerreotype process at the School of Arts (the precursor of the Athens School of Fine Arts) are connected with the name of Frenchman Philibert Perraud (1815-?)1 who arrives in Athens around the end of 1846. Perraud’s art impresses Queen Amalia, who invites him to photograph the Palace in 1847.

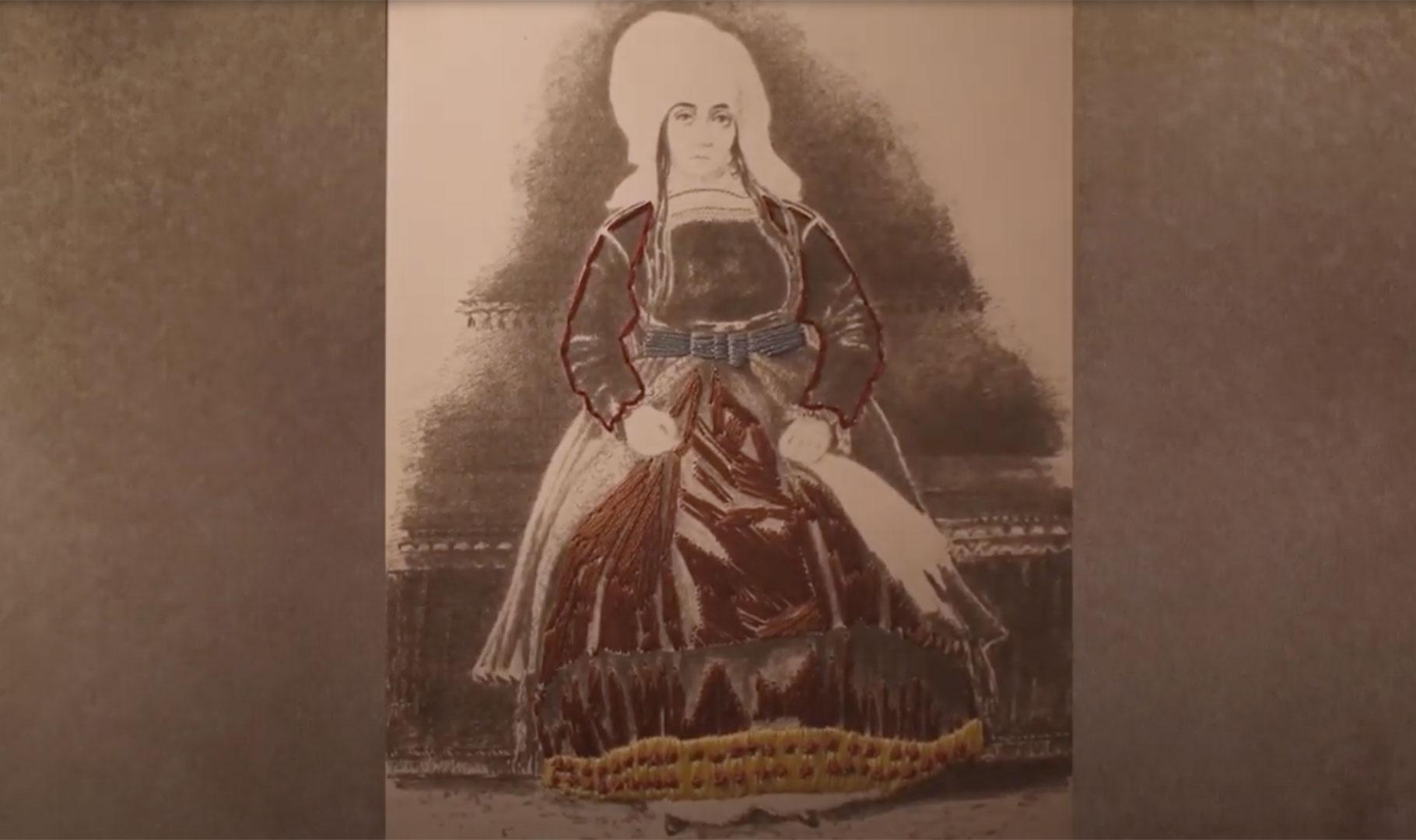

Among the first of Perraud’s daguerreotypes is the group portrait of the Ladies-in-waiting that accompany Queen Amalia and are in charge of the observance of protocol. It is not only the ladies who arrived with her from Oldenburg who hold a special place in the Queen’s heart and court, but also the women originating from historical families of fighters in the independence war of 1821. As Ladies of Honour, ranking higher than the rest, they wear the costumes of their own home of origin.

Several years later, in a photograph of 1912, the Ladies and Demoiselles of the Lykeion ton Ellinidon are immortalised as simulacra2 of the Ladies of the Court of Queen Amalia. The characters arrange themselves in a tableau vivant, dressed in “national” costumes, “as the ladies in the Court of Amalia wore them”, writes the newspaper Embros on January 7, 1912. The stylised snapshot is from the celebration of the cutting of the New Year’s pita at the Municipal Theatre.

Even if the “image” is not a reflection of reality but a simulation of it, even if it is posed by other persons in other clothes, even if it is more a representation of the past in the present, in the end the Ladies and Demoiselles of the Lykeion ton Ellinidon imprint the characters they impersonate on to our historical consciousness, while the photograph itself – like any photograph- “survives death, in order to remind us” (Meraklis, 1989).

- 1. “A skilled French painter arrived recently in Athens, and all who saw his works were very impressed. Her Royal Majesty our Queen had the pleasure of commissioning a painting of the Royal Palace in order to offer it to His Royal Highness Prince Leopold, who lived there.” Tahypteros Fimi, December 16, 1846

- 2. “simulacrum, i, n. (from simulo, as in lavacrum from lavo): image, effigy, likeness, replica, facsimile, imitation. 2) image, double, reflection (in water, mirror, sleep etc.) 3) traditionally, a picture or statue. ”Latin-Greek dictionary / first compiled and published by Heinrich Welrich of Bremen, Germany, with the second ,third and fourth editions amended and enriched in words and meanings by Stef. A. Koumanoudis, in Athens, K. Antoniadis and S. K. Vlastos Publishers, 1884, p.369.

The work of Maria Kotsou literally and metaphorically connects the Ladies of Amalia’s Court with those of the Lykeion ton Ellinidon. Through the virtual weaving of the two photographic representations, she connects the pieces of two different eras in her own unique way. In addition, by embroidering parts of the pictures which hold particular significance for the garments of the time, she attempts to give artistic visibility to the rich adornment of the clothes worn in the picture. At the same time, she employs the shape-forming properties of thread and embroidery, to create the illusion of a third dimension and bring both the people and their garments to life.

Portraits, whether painted or photographed, are unarguably incontestable documents of their time. The visual artist, however, looks beyond their value as evidence and converts the “images” of people to embroidered memorabilia. In her works she often uses elements of embroidery, weaving and other related arts in order to underline the need to preserve folk handicrafts. But in this case she uses “traditional” techniques and materials in combination with modern visual methods like stop motion animation, blurring the lines between “traditional” and modern. So, thanks to the fast frame rate of animation, the embroidery – an essentially time-consuming activity- is executed at high speed.

Finally, Kotsou highlights the ways in which modern art often co-opts “traditional” arts or intertwines with a plethora of “traditions”, contributing in a way to their coexistence on equal terms with the Fine Arts.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Maria Kotsou

Mary Thivaiou

Valeria Makri

Elektra Stampoulou

Penny Saccopoulou – Valtazanou

Zoi Kona

Nikos Saridakis

Tania Veliskou

National Historical Museum, Athens, Greece, and the Curator Androniki Markassioti, "B. Papantoniou" Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation, its President Ioanna Papantoniou and its Collection Manager Aggeliki Roumelioti, “Lucy Bratzioti” Publishing