Bloomers. Short stories of women’s fashion.

After veteran fashion editor Diana Vreeland became the first to introduce fashion into museums, starting with the Yves Saint Laurent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1983, more and more museums –especially larger ones– have aimed to organise exhibitions dedicated to haute couture designers or fashion houses. The exhibitions become box office blockbusters, while also provoking conversations about how meaning is produced in a garment museum or accentuating the clash between the display of a spectacular extravaganza and a meaningful exhibition originating from research into clothing.

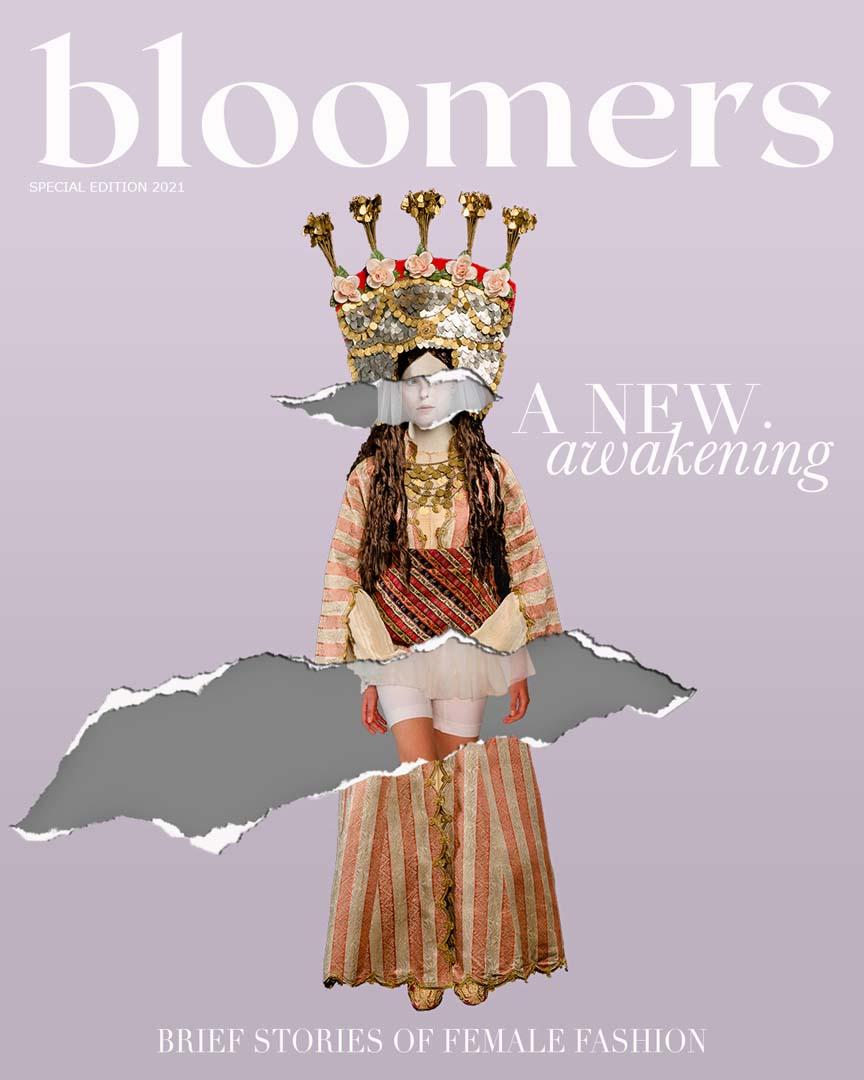

So with the recent focus on the relationship between museums and fashion, Alexandra Anagnostopoulou sets in motion a subversive experimentation through her work “Bloomers”: she transforms the potential “content” of a museum’s exhibition to the “content” of a fashion editorial on the theme of the female vraka (baggy trousers), which is encountered –in different variations, or lengths– in the East and the West during the 19th century. At the same time, by making leaps through time, she arrives at the first women’s sportswear as well as at its current equivalents: spandex garments and cycling leggings.

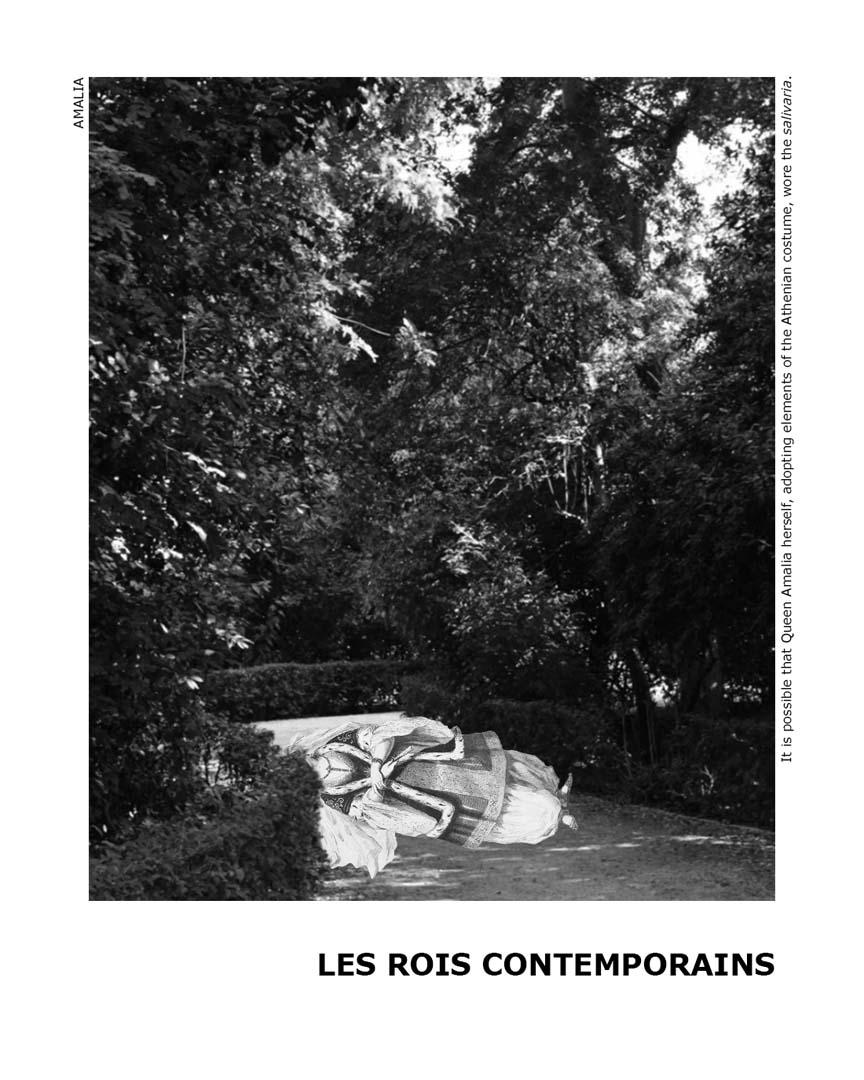

Elements that reveal the cultural “movement” and the bidirectional influences between the East and the West can be found in various aspects of 19thcentury life, while they are also reflected in clothing. In some Aegean Sea outfits with a “foustani” (dress), -like for example those of Astypalaia or Nisyros- one can see hints of Western influences, whereas others, like those of Karpathos with a “kavadi” (coat) and ankle-length “vraka” (baggy trousers)point to the sartorial habits of the conqueror. On the other hand, the “vraka” is also part of the ruling class costume of those Christian men that did not wear the “Frankish” clothes, while it is worn by Greek women as well, in different variations and on different occasions, as can notably be seen in the depiction of the “Athenean bride” by Dupré. Τhe phenomenon of cultural osmosis is reflected in the vraka, as it is one of the ways in which the Turquerie’s ottoman style in general infiltrates Western “fashion”, as it is considered comfortable, spacious and a garment that frees women from natural restrictions.

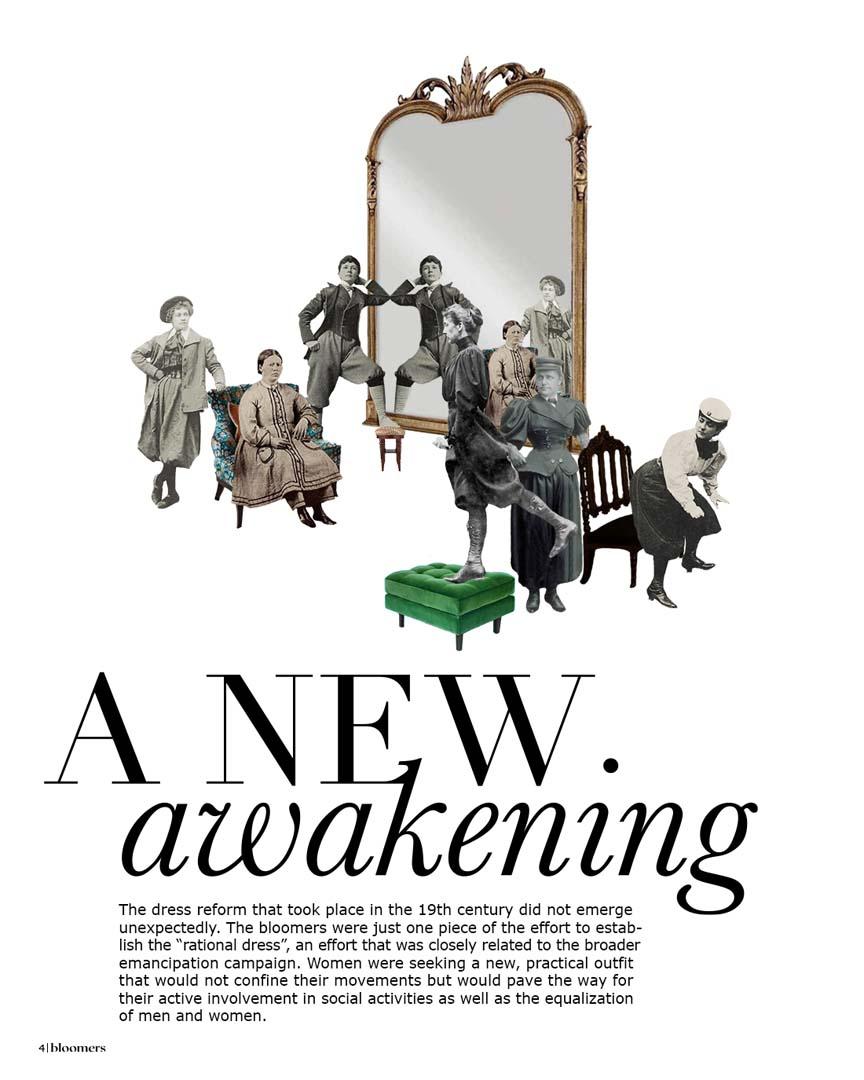

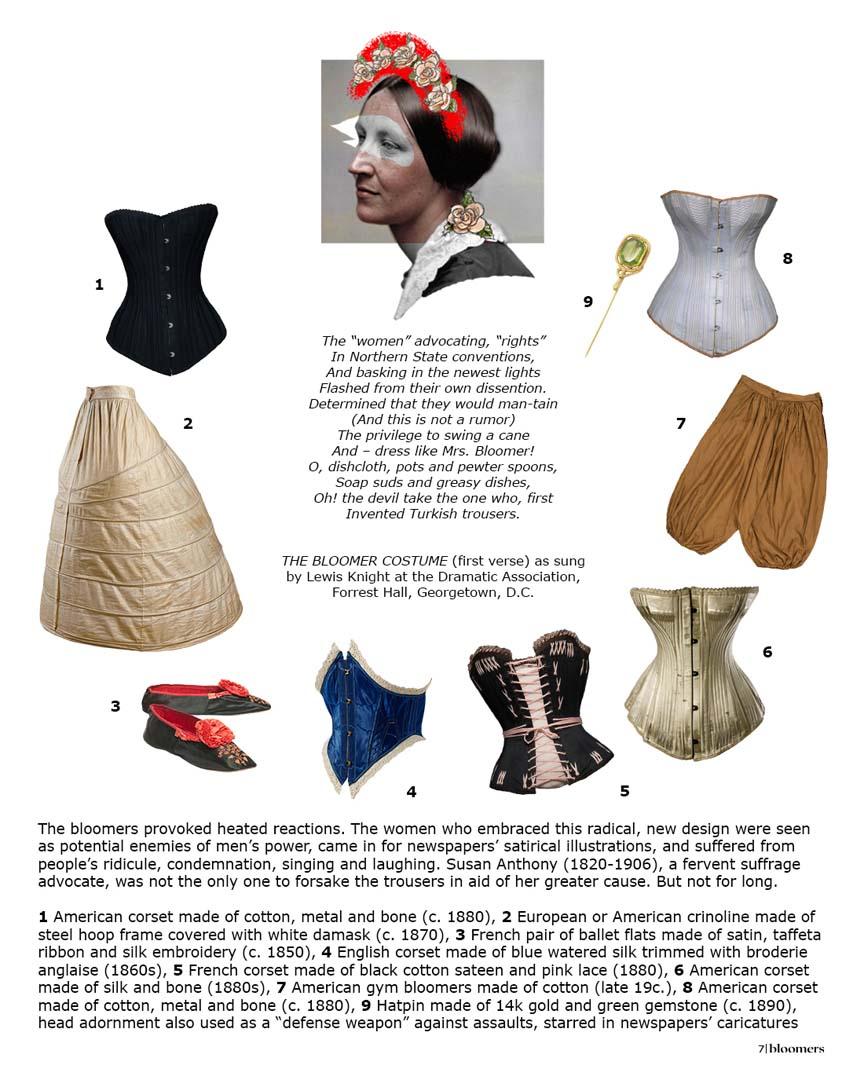

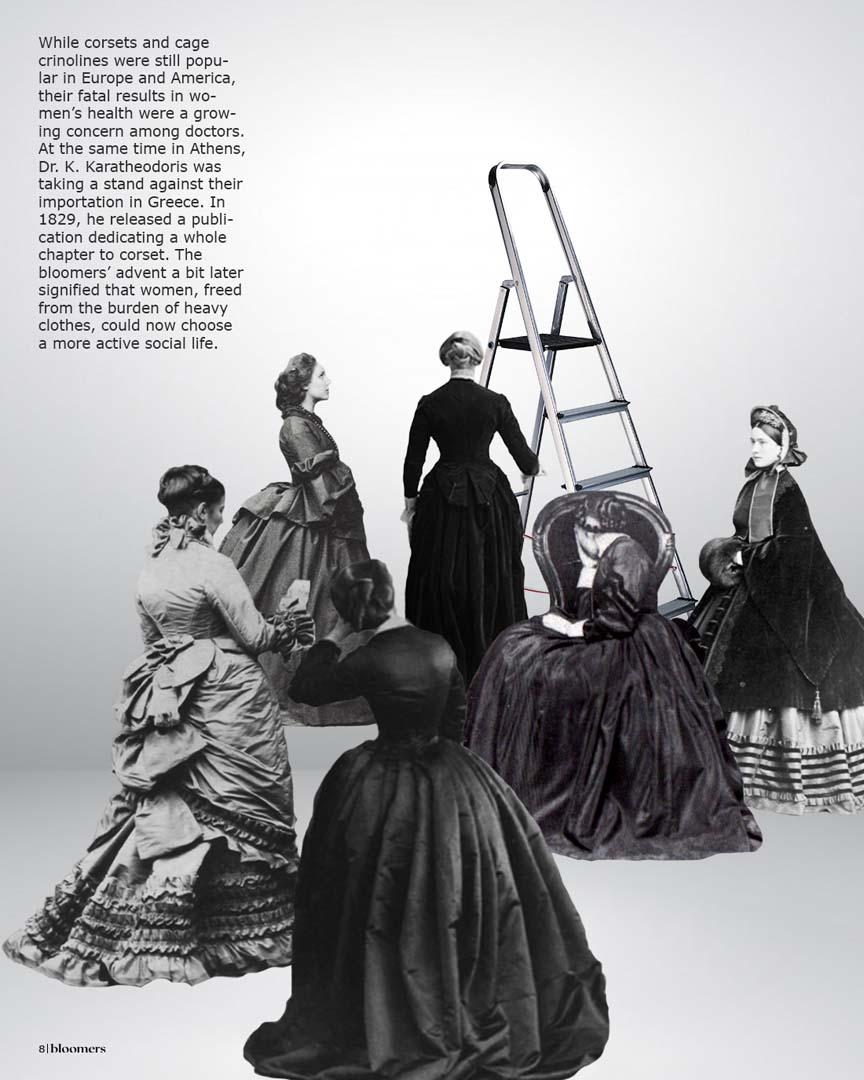

In the 19th century, in Europe and in America, corsets with metal or bone supports that compressed the ribcage and made the waist look thinner, combined with crinolines and the voluminous and heavy dresses, confined women to rigid postures. Beyond the devastating consequences on their health however, the corsets and crinolines were also an impediment to any “activity” women might do outside the home, thus reinforcing the differences between the genders.

It is therefore not strange at all that the prospective importation of the European fashion for form-fitting garments becomes a concern for the Greeks, too, as early as the first decades of the 19th century. During a meeting of the Paris Greek Committee (1828), Doctor Konstantinos Karatheodoris proposes that the book by the Frenchman Constant Sancerotte under the title Conseils sur la santé, ou Hygiène des classes industrielles (Recommendations on the Health or Hygiene of the industrial classes) be translated and adapted to the needs of the Greeks, noting that “a chapter on clothing should be added,, so that Greek women take care with the wearing of corsets”. A year later Karatheodoris, with the support of the Greek Committee, publishes a manual for the public, drawing information from Sancerotte’s publication. In a column of the third chapter of the book titled On articles of clothing for the different parts of the body”, he writes: […] All over civilised Europe, women tend to wear over their breasts an article of clothing called a corset, which goes down to their abdomen. This beautifies the body and makes the waist very slim. The use of this article is completely unknown in Greece and maybe I shouldn’t mention it at all. […] I thought it is necessary to forewarn women that its use is very dangerous, [...] because it can cause serious and incurable illnesses, including tuberculosis. […] My opinion is that it must never be imported into Greece because of the countless and incurable harms it causes”.

On the other hand, as early as the 18th century, Europeans are fascinated by the clothes of the East. What contributes decisively in the dissemination of the Turquerie in the West are the travel impressions of the chargés d’ affaires in the Ottoman Empire and also the travel writings of women who come in contact with the “exotic” East. A typical case is that of the English Ambassador’s wife Mary Wortley Montagu, who, during her stay in Constantinople from 1717 to 1719, recorded several moments from the private lives of Ottoman women. Men and women of the upper class in Europe wear turbans, kaftans and belt buckles and pose for painters of the time, while Lady Montagu herself is pictured in eastern clothes and vraka in a painting by Jean-Etienne Liotard.

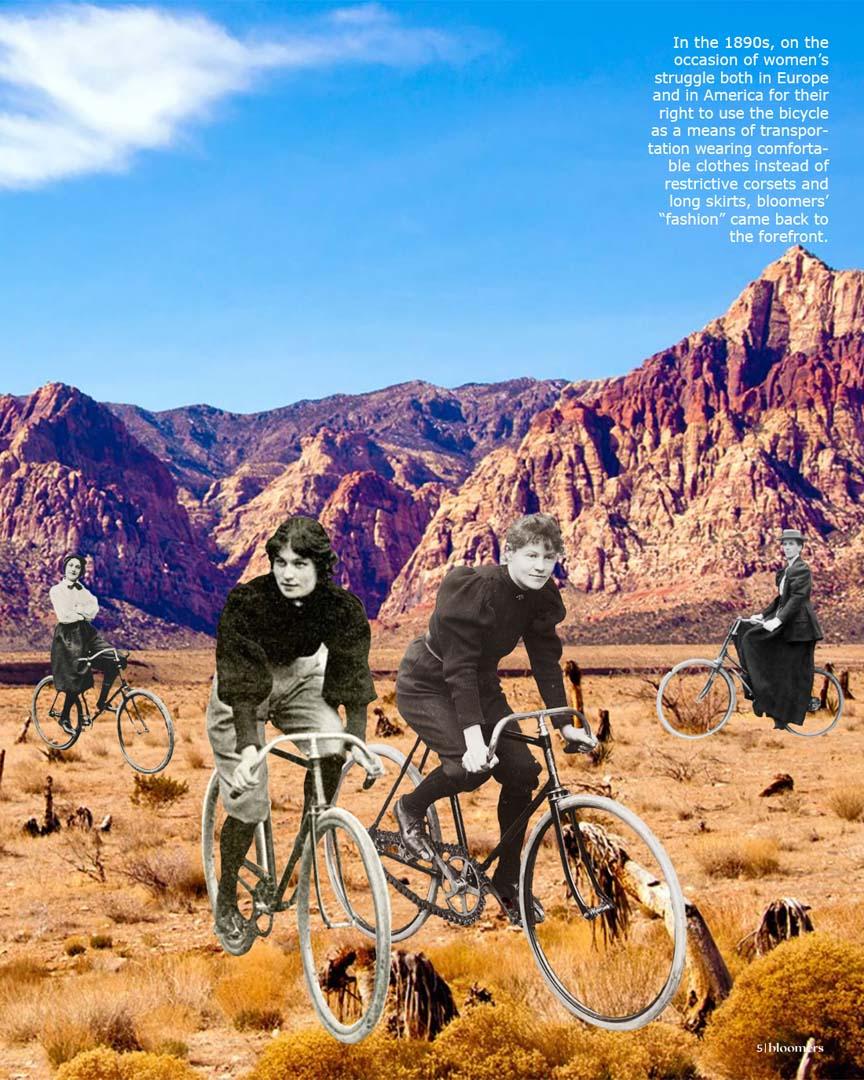

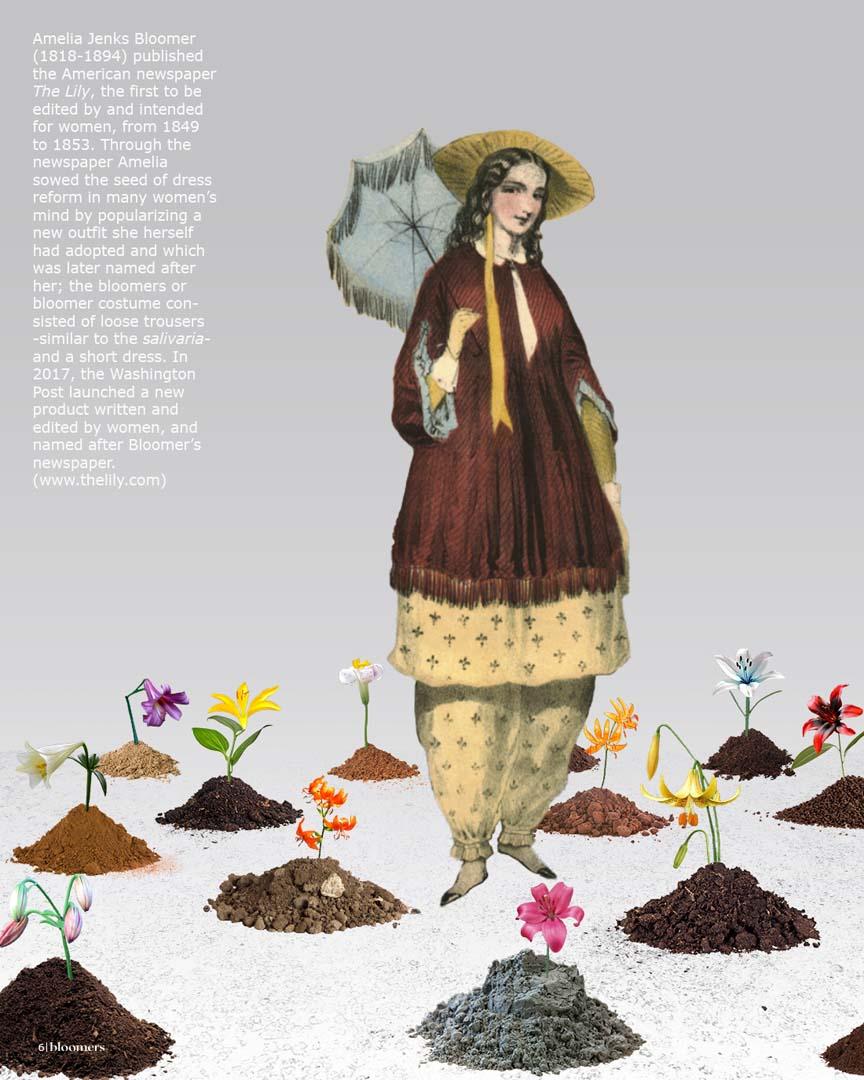

“Turkish pants”, as the baggy trousers gathered at the ankles are usually called in the West, continue to attract attention much later. Around 1850, the American Amelia Bloomer, overturning the contemporary standards for women, adopts in the place of the corset the radical for the time ensemble that took her name: bloomers, a combination of spacious baggy trousers and a knee-length short coat. Although the outfit was considered less “constraining”, initially facilitating movement and thus opening the way for women to participate in public life and achieve equality with men, the fashion for bloomers was not widely accepted at the time. It will return to the spotlight in the 1890s in Europe and in America as women fight for the right to use bicycles as a means for transportation, wearing comfortable clothes instead of suffocating corsets and long skirts. Within our country, of course, on the occasion of the first Olympic Games in1896 and the establishment of cycling as a sport, Kallirrhoe Parren writes on April 24, 1894 in an article in the Ladies Newspaper titled “Women cyclists”: “we adopted the bicycle because we considered it fashionable”, noting that this means of transportation is inappropriate for the Athenean woman who is “elegant, so fond of beauty, so artistic in every movement». Two years later she republishes from the French a text by the journalist Baudry de Sonnier on the issue of female cyclists’ “outfits”, but without expressing a personal opinion.

The German byzantinologist Krumbacher also notes a lack of femininity in women who wear baggy trousers, when he visits the island of Lesvos in 1886: “Many lower-class women wear ankle-length baggy trousers, differing from the men’s ones only in their greater length. A woman dressed in that way, a Vrakou, as the locals call them, seems hideous and English women asking for liberation and making noise about the general introduction of menswear could be cured of their mania here”.

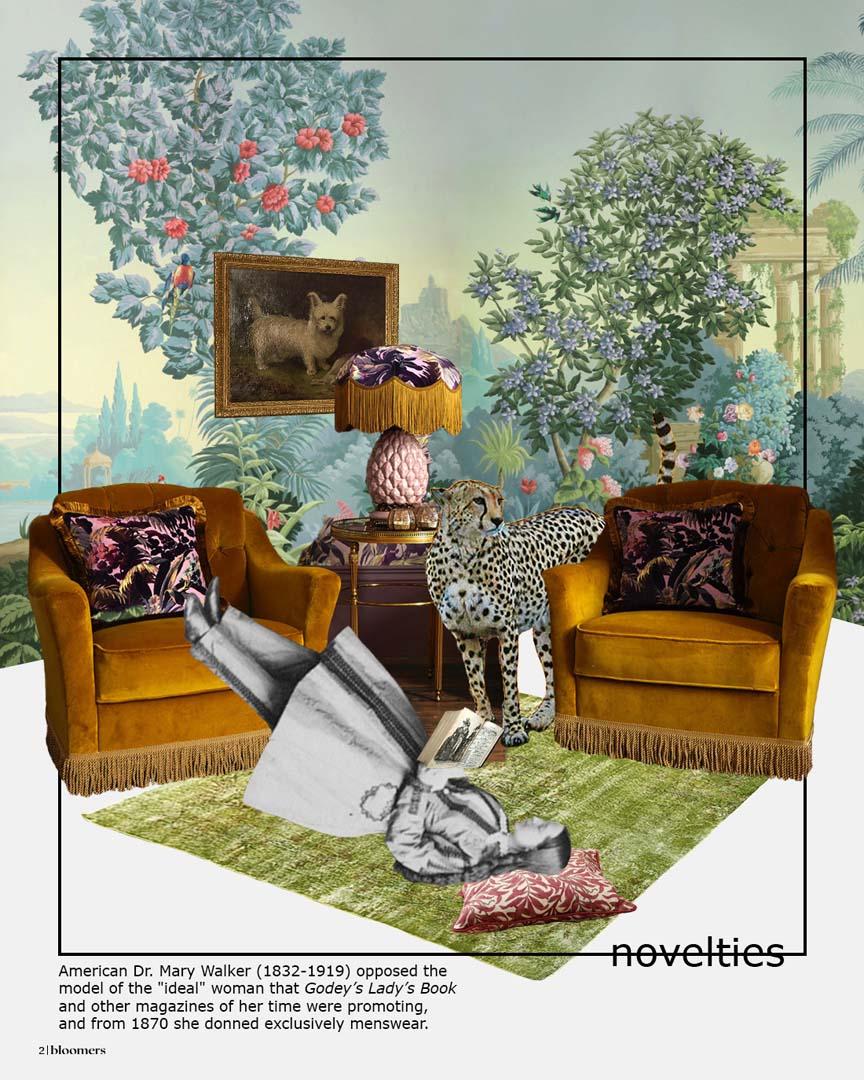

Using various sources for illustrations with “revolutionary” for their time clothes as “objects” and the pages of a magazine she names “Bloomers” as a “space” Alexandra Anagnostopoulou proposes a different “reading” of the museum. More specifically, the artist, in the role of a contemporary fashion editor, develops short fashion stories, worth the attention of a costume museum, but in the visual language and the format of a modern magazine.

Her work moves along two axes, though it jumps back and forth in time without any continuity regarding the evolution of the sartorial types she refers to. So one axis is developed through representative sartorial shapes that were in some way “revolutionary” for their time or were connected with the struggle for the emancipation of women. The other, postdated, axis follows ready-to-wear and haute couture suggestions, set up as parallels to “equivalent” garments of the past or having as only common points of reference their typology and occasionally the circumstances of their use.

In this context, searching through the “duration” of time (in the Bergsonian sense of la durée), she looks for shapes that are reflected in the past, thus creating “pairs” of outfits, albeit ones that are non-continuous, autonomous or juxtaposed to each other. An indicative example of such an “odd couple” is on the front cover of the magazine. It features an outfit that imitates the “Athenean bride” by Dupré –an ensemble that has a large vraka on the inside– while a picture of A.F. Vandervorst’s 2019 suggestion for a bridal outfit with leggings leaps out from a tear in the cover.

Using an idea from the work of Brazilian photographer duo Marcos Florentino and Kelvin Yule for an advertising campaign for Portuguese bridal dress house Emannuelle Junqueira, she places Amelia Bloomer in the centre of page 6, surrounded by flowers of the lily family, as the first newspaper published in 1849 in the US by Bloomer herself was called The Lily.

Again, drawing inspiration from group photographs of models, where the setting consists of various “props” like mirrors, boxes that form different levels, chairs, ladders etc., she creates two corresponding arrangements: one with bloomers as the point of reference (page 4) and the other centered around long dresses and crinolines (page 8). In fact, in the second case she deliberately uses a ladder as a prop, but leaves it “unused”, to imply the difficulties caused by the wearing of crinolines when passing through a door, climbing into or descending from a carriage, sitting down, and so on.

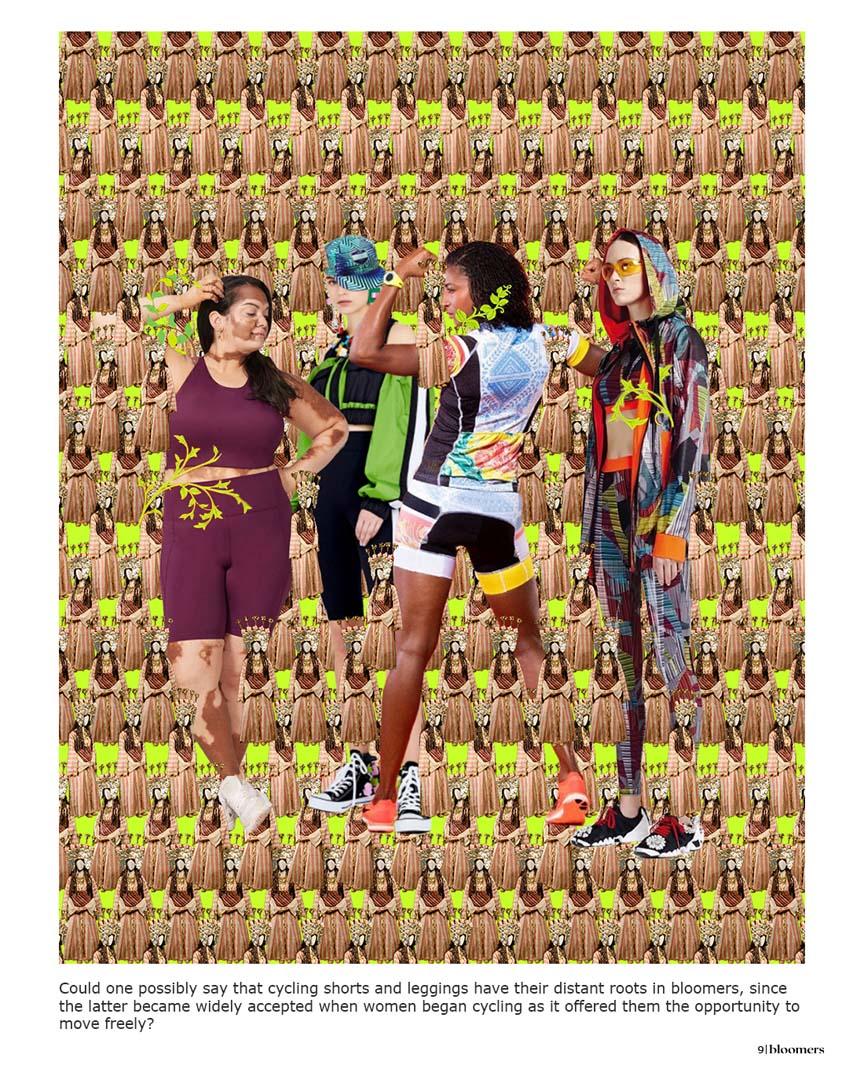

On page 9 she “jumps” to cycling shorts, which in the last years have transcended their original role as active wear and have become a trend in daily wear, combined with large blouses, oversized blazers, and even high heels. Her choice to place models of colour in the arrangement is not at all coincidental. Beyond emphasising the diversity that has been promoted more by the fashion industry in shaping the standards in recent years, the snapshot is a clear reference to the work of African-American artist Kehinde Wiley, who was commissioned in 2018 to paint the official portrait of the 44th President of the United States Barack Obama for the National Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution. In his works, Wiley replaces noblemen, aristocrats and other historical figures featured in famous paintings of the 19th and 20th centuries, with portraits of people of African origin whom he meets in the street, placing them in some way –as he says– in the sphere of power, thus emphasising the absence of African-Americans from historical and cultural narratives. Additionally, the artist develops a tapestry in the background that repeats the image of Dupré’s bride in an almost fluorescent green tone, which has recently been in fashion. This approach is influenced once more by the Wiley’s ’s visual practice of creating a multi-coloured background with motifs from old tapestries behind the people pictured, so that the motifs mingle with the models as if they threaten to make them disappear while simultaneously giving birth to them.

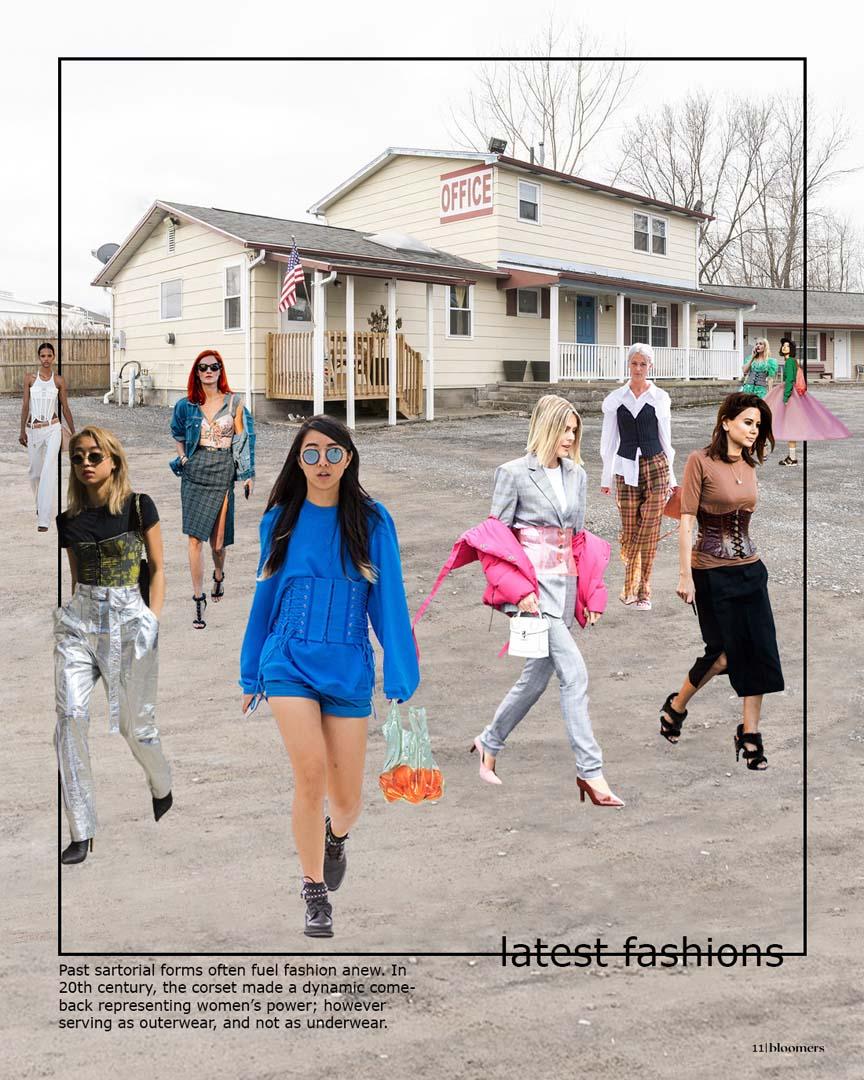

With her composition of page 11 she underlines how the use of garments changes over time, and more specifically how the corset has moved from underwear to outerwear. Inspired by Balenciaga’s 2019 advertising campaign, she creates a collage of street-style photos.

So, in this way Anagnostopoulou, moving from the past to the present day and from here to there and back again, like the “back-and-forths” of fashion, brings through her work the “content” of an exhibition to the coffee table in our living room.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Alexandra Anagnostopoulou

Zoi Kona

Alexandra Anagnostopoulou

Penny Saccopoulou – Valtazanou

Tania Veliskou

"B. Papantoniou" Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation, its President Ioanna Papantoniou, Aggeliki Roumelioti, Collection Manager and Maria Papadopoulou, Documentation & Publications Department