Acumen

Through a work of remarkable density that is inspired by the Elisavet Moutzan-Martinengou’s Autobiography, Aggeliki Bozou approaches the ways in which clothes reflect the social ranking of a woman, compose her gender identity and delineate power dynamics at the time of the Greek Revolution. Furthermore, with references to modern-day reality, through her work she prompts discussions around the timeless and always relevant demand for equality between the two genders.

The notion of equality between the two genders is at the epicentre of Rigas Velestinlis’ thinking. In his work New Political Administration1 (1797), where he sets the “foundations of freedom, of security and of happiness” of subjugated nations, he expresses the need for equal participation of boys and girls in education as a condition for the intellectual awakening of the Race, while at the same time he reflectively adds to his positions the right of women to bear arms if needed.

These ideas can be found in the Autobiography of the noblewoman from Zakynthos Elisavet Moutzan-Martinengou (1801-1832), written at a time and in a society that were not favorable to such views.

The exclusion of Greek women from the public scene and their submission to the rules of married life before and during the revolutionary period is documented by many foreign travellers who visited Greece. As far as the position of women is concerned, specifically in the society of Zakynthos, we draw information from the letter that John Carswell2, a Corporal in the 90th Regiment of the Light Infantry of the British army in Zakynthos, sent in 1824 to his sister Martha. In this letter Carswell also addresses his beloved Isabella. In order to romanticise the distance between them, he refers to the Zakynthian “tradition” by which women do not meet their husbands in person before the wedding. This fact is also confirmed by the Irish doctor William Goodison3, who served in the 75th Infantry Regiment of the English in the Ionian islandsbetween1814 and 1821, as well as by the English traveller Lady Hester Stanhope4, who visited Greece in 1810.

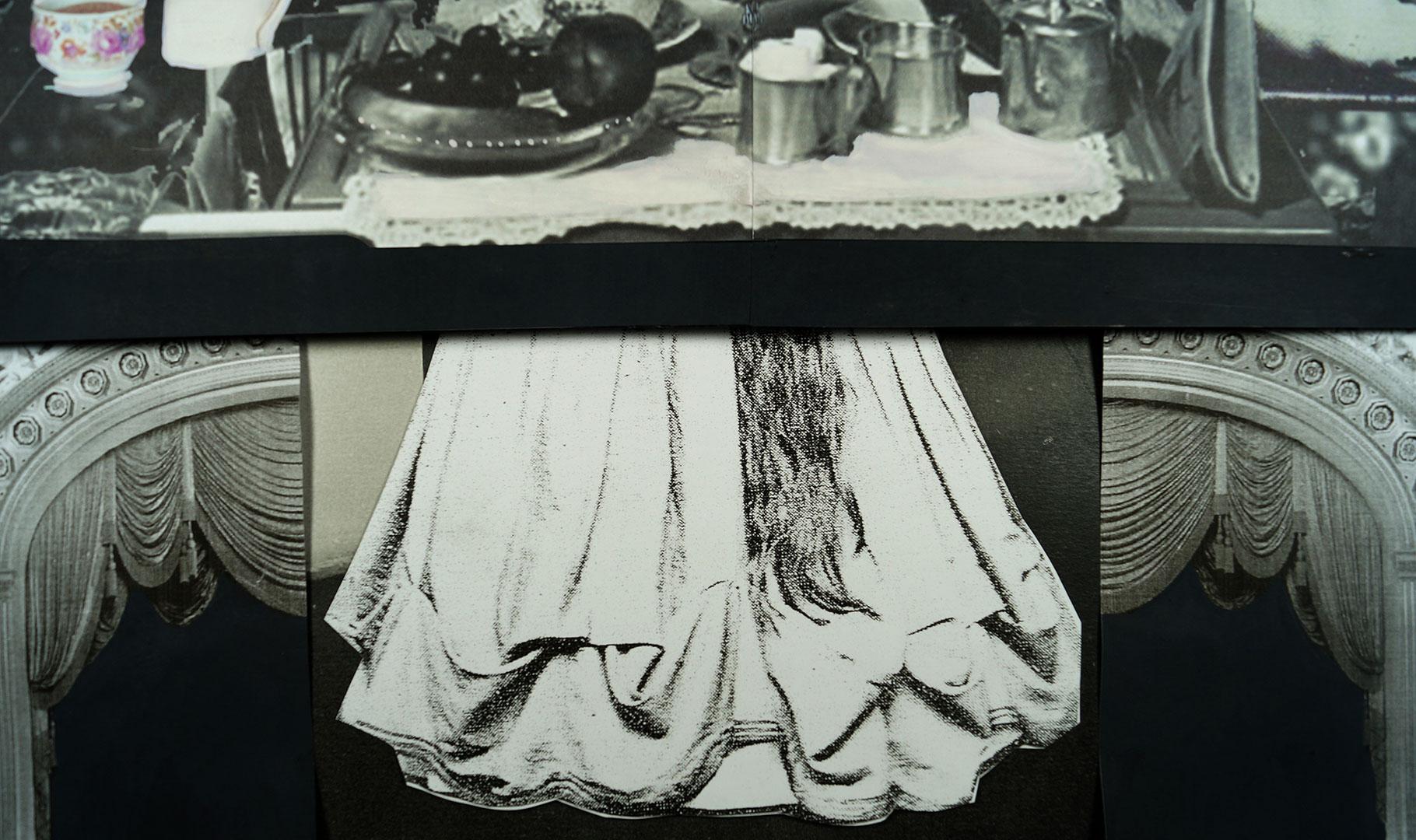

The picture captured by Elisavet’s memoirs is exactly this: that of a woman who lives behind the tzeloutzies5 and whose gender prohibits her from participating in the liberation war of the Greeks. Furthermore Martinengou’s reference to her long dresses indirectly and implicitly demonstrates the limitations deriving in those days from female clothing, but also how clothes can function both as a rule of etiquette and as a reminder of that rule and how they can reinforce the differences between genders. So, in pondering her options for liberation from the bonds imposed by her patriarchal family, her social rank, and by extension, Zakynthian society in the first decades of the 19th century, she even contemplates suicide.

Indeed, in reviewing the chronicle of the liberation War, one finds many cases of women who eventually manage to overcome the restrictions of their social position. According to testimonies, they come up with various tricks, to the point of dressing in male clothes to access to the war without being recognised. (Like Tassoula Gyftogianni (Gyftogiannena)6 from Messolonghi). Many of these women acquired almost mythical status, which in the passing years was praised in speeches demanding the emancipation of women. A typical example is the Ladies Newspaper, where Callirrhoe Parren glorifies the participation of women in the Revolution, placing their bravery and heroism in the service of then-modern feminist goals.

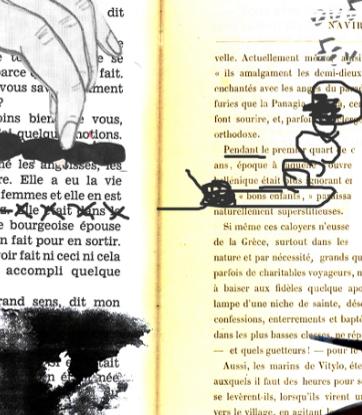

Martinengou’s text has been described as a silent voice of protest. Besides, it was only published by Elisavet’s son in 1881, fifty years after her premature death, in a volume alongside his own poems, and was an abridged version, as he himself states in his Epilogue7.

- 1. “Everybody without exception have the obligation to be literate. The State has to establish schools in all the villages, for male and female children. Literacy brings prosperity that makes free nations glow. {…} (Rights of Men [or Declaration of human rights], article 22) “All Greek men are soldiers. All should undergo arms and target training. All should be taught tactics. Even Greek women should bear bows, if they are not proficient with riffle.” (The Constitution – Principle of the Statutory Act and Soul of the Administration, article 109)

- 2. “|27 Greek Woman Courts to the men at a distance tha* ar* not |28 allowed to See one nother* till monce that ar* Marr[i]ed.” From the original text of the letter: see Vassilis Chryssovitsiotis, “Unpublished private letter from Zakynthos to Paisle, Scotland in 1824: John Carswell to Martha Carswell” Ionian Analects, vol. 5, 2015.

- 3. “The Zante women are still more closely confined than those of other islands. Most of the windows are defended by a thick lattice work, which projects into the street, giving them more the appearance of so many prisons, or homes of correction; they are thus wholly removed from public view; [...]” William Goodis(s)on, A Historical and Topographical Essay upon the Islands of Corfù, Leucadia, Cephalonia, Ithaca, and Zante: with Remarks upon the Character, Manners, and Customs of the Ionian Greeks; Descriptions of the scenery and remains of antiquity discovered therein, and reflections upon the Cyclopean ruins, London, 1822, p. 186

- 4. “[…] Among the higher classes. The unmarried females are kept much shut up in rooms with blinds to the windows, and are often betrothed without being see by their future husbands […]”, Hester Lucy, Lady, Stanhope, 1776-1839, Travels of Lady Hester Stanhope; forming the completion of her memoirs, London, H. Colburn, 1846, p. 25

- 5. “Tzeloutzia (jalousie), an oak window blind that prevented women from being seen from the outside. Such oak latticed screens remained in the women’s sections of some churches.” In Leonidas C. Zois (1865-1956), Historical and Folkloric Dictionary of Zakynthos, editions O Foskolos, Zakynthos, 1898, p. 467.

- 6. Gyftogiannena, just before dying, said to the women who were keeping her company: “Girls, I am dying. Take this key to my trunk, there you’ll find a good outfit of mine, and I want you to bury me in it. Take my blessing!” So, when she died, they opened the trunk and found underneath not women’s but men’s clothes, those that she wore during the escape, with the selahi (leather belt for carrying weapons) and the tsarouhia. So Gyftogiannena was buried in the clothes of a warrior. Filippopoulos, Nikitas Chr. (2002). Messolonghi in the passage of time. Dapia p. 132.

- 7. “What was left out, as I mentioned in the preface, from the autobiography of my late mother, consist of certain family events, of her first impressions as a child, of affections and dislikes towards family and certain persons, and in the whole everything shows her ever-angelic soul and the premature and transparent development of the mind of my distinguished and beyond all praise mother, and they were omitted because they are of interest only to me as her son and to the closest relatives of the esteemed Moutsan family.” In “My mother, autobiography of madam Elisavet Moutzan-Martinengou, published by her son…in Athens…1881, p. 117, “epilogue”.

Recalling the autobiographical writings of Martinengou Aggeliki Bozou creates a work with a feminist tone.

The artist approaches Martinengou’s autobiography as a micro-history that intersects with the history of women’s issues and gender discrimination. In her work, the person of Martinengou becomes present only through the voiceover. The narration, however, goes beyond personal storytelling and connects to the fate of other women, the contemporaries of the autobiographer. At the same time, by creating an illusionary tale with symbolic signalling, Bozou adjusts Martinengou’s narrative and the time of its writing to modern reality. As a result, she interweaves Martinengou’s words even with pictures of present-day women. Registered in this concept is the use of scenes from the private, everyday microcosm of a woman, which bring to mind clichés about women being stuck in the role of wife, of mother, of lover (setting the table, kitchen etc.). A similar role is played by the sounds interspersed through the video (e.g. washing up, a crying baby, the sound of high heels).

Furthermore, the censorship imposed by Elisavetios on his mother’s autobiography does not remain unobserved by the artist. In the imaginary world that Bozou creates – fulfilling, in a way, the implied aim of the author to publish, as she herself declares, her work - she does not hesitate to make her own speculations about the things that some women may suffer today and which are often hushed. Hence, she dares to add pictures that imply gender-based violence, like sexual or physical abuse. Following the same reasoning, the choice of Acumen (sharpness of mind) as a title for her work is not at all arbitrary. The use of this term takes aim yet again at the position of many women in general who, although their mind is agile, are - due to their gender – left out on the fringes or unable to react to any form of suppression.

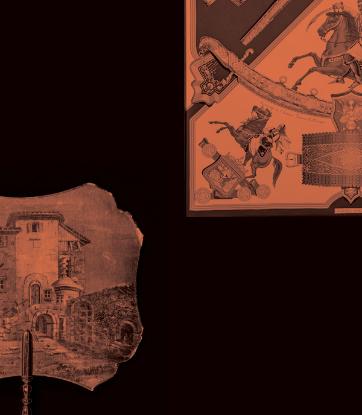

Moreover, by drawing on illustrated material that captures symbols of protest, opposition and sacrifice from different time periods, but also female figures, she creates a reminder of the armed action of certain women and their participation in fights and rebellions for freedom and emancipation (i.e. fist, tanks etc./ Laskarina Bouboulina, Antonousa Kastanaki1, Frida Kahlo and others).

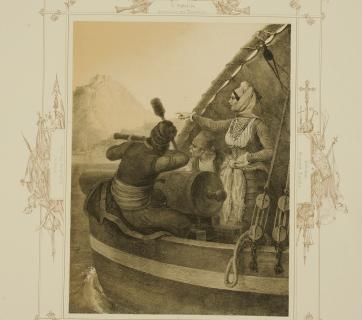

Finally, she focuses on the phenomenon of the occasional reversal of gendered dress codes (cross-dressing). Namely, using the idea of paperdolls she alternates, at a blistering pace, female with male clothes on the body of a female paper figure. Among the clothes that she chooses to use is the pleated dress commonly found in the islands of the Argosaronikos Bay that Laskarina Bouboulina wears in a 1852 lithography by Peter von Hess, where the heroine blockades Nafplion in the summer of 1821.

She thus gives the public the choice to interpret at their own will the role that clothes can play in the “creation” of sex identities, but also to wonder how the women that actively participated in the independence War might have been dressed. Maybe in the way that the heroine of the novel Eleni or Nobody wonders in her dream about Bouboulina.

“Standing on the prow, attacking the unconquerable Nafplion with her fleet, she would show the cannoneers where to aim by raising her right arm. She was not wearing the clothes from her famous painting, though, but the clothes of whispers and secrecy. It was just as the women on their doorsteps would insinuate when I would hear them as a child at the close of the day, but only now did I understand the meaning of their words: ''One cannot enter the act of war in a woman’s clothes''. They can handle neither their arms nor their minds properly in that way. And worse, the mismatched women’s clothes would give a target to the enemy, bringing bad luck to their own people. So, they would conclude, but without having seen her in the moment of combat, of course, that Laskarina must have gone on and off the ships in her skirts and golden scarves, but while she was in charge, she couldn’t but have worn men’s clothes, sometimes those of her first husband, other times those of the second, both of them killed. I dreamed of her leading the cannoneers, dressed in the bloodstained clothes of an unfairly killed and beloved man. […] The Lady withdrew her gaze from the target for a moment, turned to me and told me to continue to dress as a man because this way I would learn twice as much from both men and women”.

Excerpt from the novel by Rea Galanaki, Eleni or Nobody, Kastaniotis publishing, Athens 2004, pp. 16-19. The work is based on the life of the first Greek female painter, Eleni Altamoura-Boukoura (born in Spetses, 1821), who dressed as a man and under the pseudonym Chryssinis Boukouras managed to study painting in Italy.

- 1. Antonousa Kastanaki( born in Kera Kissamou, 1844) fought in the revolution of 1866 in Crete, wearing, it is said, the Cretan men’s costume. Her face is known from the front cover of the Italian magazine “L’ Emporio Pittoresco” of the 5thSeptember 1868, in an article about the Cretan Revolution of 1866-1869, written by the philhellene Dora d’ Istria.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Aggeliki Bozou

Thanos Kosmidis

Petros Stamelos

Penny Saccopoulou-Valtazanou

Alexandros Kaklamanos

Zoi Kona

Tania Veliskou

the National Historical Museum and Natassa Kastritsi, Head Curator of Collections