Based on the idea of “Pocket Museums”, which condense information and narratives into a limited space, the exhibition “18.21m². The war in the salons” takes place in a micro-environment with few exhibits and summarises basic aspects of the philhellenic trend, with parallel references to and extensions into contemporary reality.

The 1821 war is not just about what happened in the geographical area where the modern Greek state would rise. During the second half of the 1820’s, the War of the Greeks for liberation evokes feelings of sympathy, primarily among the liberal-minded circles of the western world, creating a movement of unprecedented momentum and impact that became known as Philhellenism.

Apart from the practical solidarity of many Philhellene volunteers towards the fighting Greeks, the “Greek Cause” rouses the European and international press, inspires intellectuals and artists, and at the same time creates new trends that are expressed through “fashion” and embrace more or less every aspect of society life.

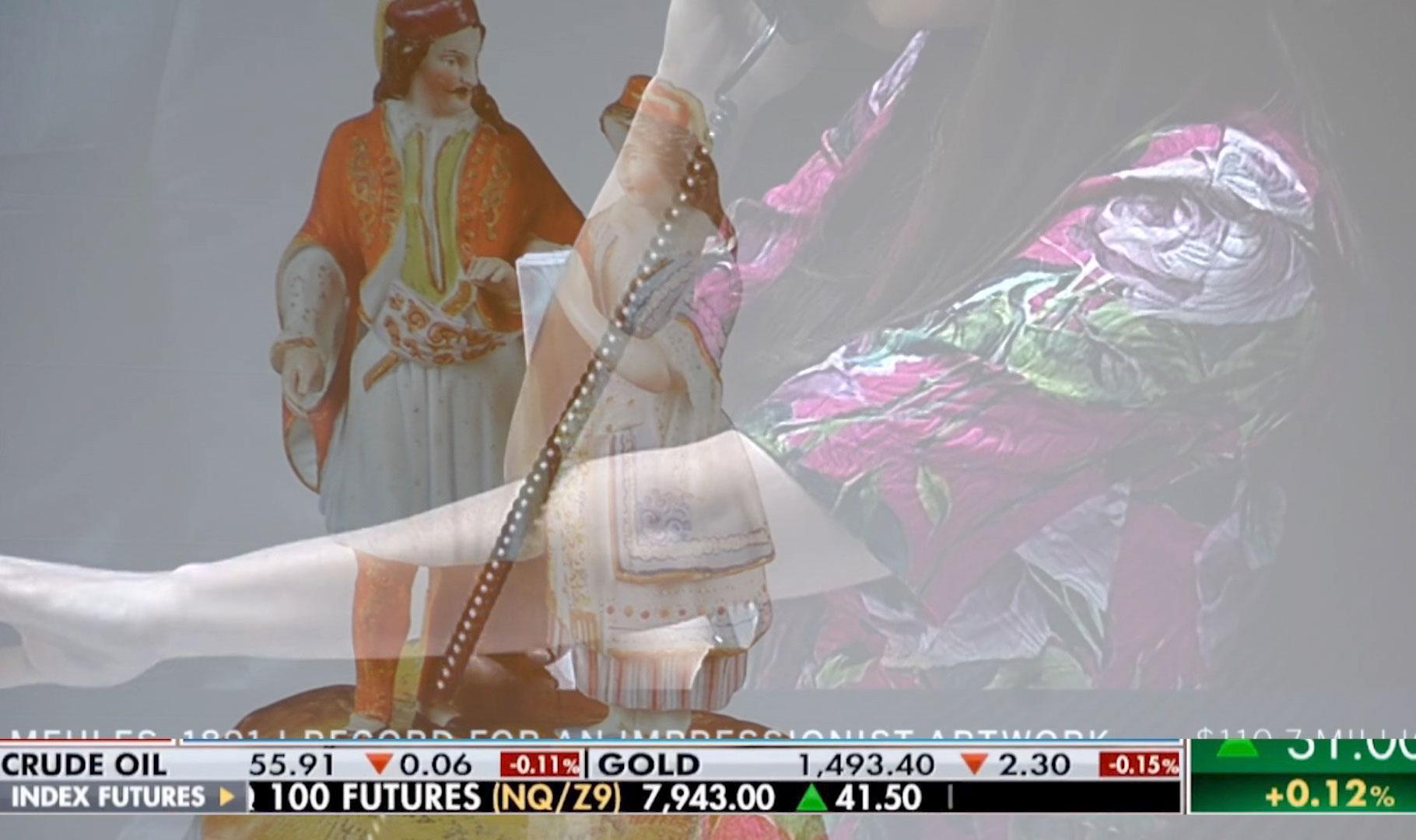

Scenes depicting hand-to-hand combat between Greeks and Ottomans, as well as the political affairs of the time, come to life on porcelain dinnerware and tea sets or are gilded on clock bases and alabastrons, while the warriors’ faces are engraved on everyday objects. “There are three luxury items that are indispensable in the reception rooms of high society houses: bronze objets d’art, table-top clocks, porcelain statuettes” writes the Journal des Dames et des Modes in 1827, setting the trends for the era.

The sympathy of the Philhellenes towards the rebellious Greeks is also expressed through their personal appearance on the occasion of various circumstances. At social events organised by philhellenic committees in Europe and in America with the purpose of raising funds for the Greeks, guests often appear wearing garments à la Grecque, as for instance at the ball organised at the Park Theater in New York in 1827. Masked balls with Greek themes are also organised, like the one of Hungarian nobleman József (or Giuseppe) Batthyány in Milan on January 30, 1828.

Furthermore, quite a few will adopt elements of the Greek sartorial identity, drawing inspiration mostly from illustrated sources. On July 16, 1821, the French newspaper Le Constitutionnel advertises a famous House that sells an etching of the Greek Jeanne d’ Arc, as Laskarina Bouboulina was called in France at the time. Soon, French ladies adopt the dresses Robes de dames à la Bobelina, while their example is followed even by women in Austria and Bavaria.

In addition, after the ball organised For the benefit of the Greeks at the Vauxhall in Paris in April 1826, the Greek colours become a trend and white-and-blue “Greek” decorative bands and belts are launched on the market. “If you see white ribbons with little blue crosses {on hats}, {…} they are Greek” states the Journal des Dames et des Modes on May 5, 1826. Furthermore, the elegant French ladies of the time embroider Greek initials on their handkerchiefs and sometimes hold fans with Greek themes.

The dictates of philhellenic “fashion” in France are also followed by men, who decorate their waistcoats with blue crosses. In addition, after the fall of Messolonghi on 1826, a fabric for men’s clothing is established under the name «Gris de Missolonghi».

Inspired by the phrase “Living-Room War”, coined by Michael J. Arlen, who used it first in his book by the same title, as a comment on the “invasion” of images from the Vietnam war into the privacy of home through television, the presentation focuses on the intake and the intrusion of the “image” of the Revolution of 1821 into philhellenic circles, especially through the establishment of a kind of philhellenic “fashion”. The scenery is composed of objects with clear references to the philhellenic “fashion”, along with drawn depictions of 19th century furniture from the Parisian newspaper Meubles et Objets de Goût, creating visual stimuli that invite the visitor to imagine by association the interior of a salon of that era. It was there that decorative and functional items “transferred” the images of the War of the Greeks, while also offering a springboard, a reason or a pretext for discussion at a time when illustrated press did not exist.

The unit is framed by the video work of Mary Thivaiou, which takes us to the scene of another idiosyncratic “war”, where the main characters are the objects themselves: the “battles” that take place live, and online too, at auction houses and in bidding wars, to claim and secure collector’s items. The video investigates the “fate” of the items, as well as the phenomenon by which they are disengaged from the social reference points of their production and use and are integrated into the system of tradable art. They once again become the object of bidding -this time among their potential buyers- while they also breed further demands for authenticity or legal possession.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Tania Veliskou

Mary Thivaiou

We Design

Zoi Kona

Penny Saccopoulou - Valtazanou

Ethnological and Folklore Museum of Chrisso, “VERGOS AUCTIONS” for permission to videotape-photograph a “live” auction

Museum of the History of the Greek Costume

(Dimokritou 7, Athens 10671)

Monday - Friday 10.00 - 14.00

210 3629513