One piece of cloth - an “invented” emblem.

One piece of cloth, an improvised, “invented” emblem, is the work of the same name by Maria Varela. Using the dynamics of creative technology, the media artist creates a flag that she turns into the visual identity of the exhibition and its components, at the same time (re)introducing, through her work, the political and other uses of symbols, and commenting on their contribution to crystallising the national consciousness and shaping “national” identities.

The [military] flag, in any form, in any shape or size, in all armies and at all times, has a special place and deep importance. It constitutes a symbol of identity, unity, rebellion, moral exaltation and freedom, interwoven with a nation’s struggles. It is always at the head of every attack. The body keeps it flying and never parts from it, while everybody vows “to fight under it till their last breath and their last drop of blood”.

A common revolutionary emblem “of the land warfare forces’, as well as a flag for the “by sea” ones, are defined for the first time by the ‘Temporary Administration of Greece” during the session of the 1st National Convention of the Greeks in Epidaurus, on January 1st, 1822. Till then, -and due to the absence of a single, unified administration- there were many and various types of flags, each one bearing a multitude of symbols, depictions, inscriptions and colourings.

Apart from the battle flags of the Klephts and the Armatoloi, the standards flown at festivals, the ensigns of the navy, the banners of warlords or the first improvised revolutionary flags of land and sea military corps, even ecclesiastical pennants were recruited as flags, demonstrating in a way the confluence of religious with national identity.

Furthermore, even women’s headscarves or a simple piece of cloth –εν πανίον- could temporarily take the place of a flag. It is preferable to fly “[…] a plain piece of cloth one and a half spans wide and as long as it happens to be[…]” than to raise no flag at all, Kolokotronis writes in a letter to his brothers in Vervena, on the eve of the battle of Valtetsi.

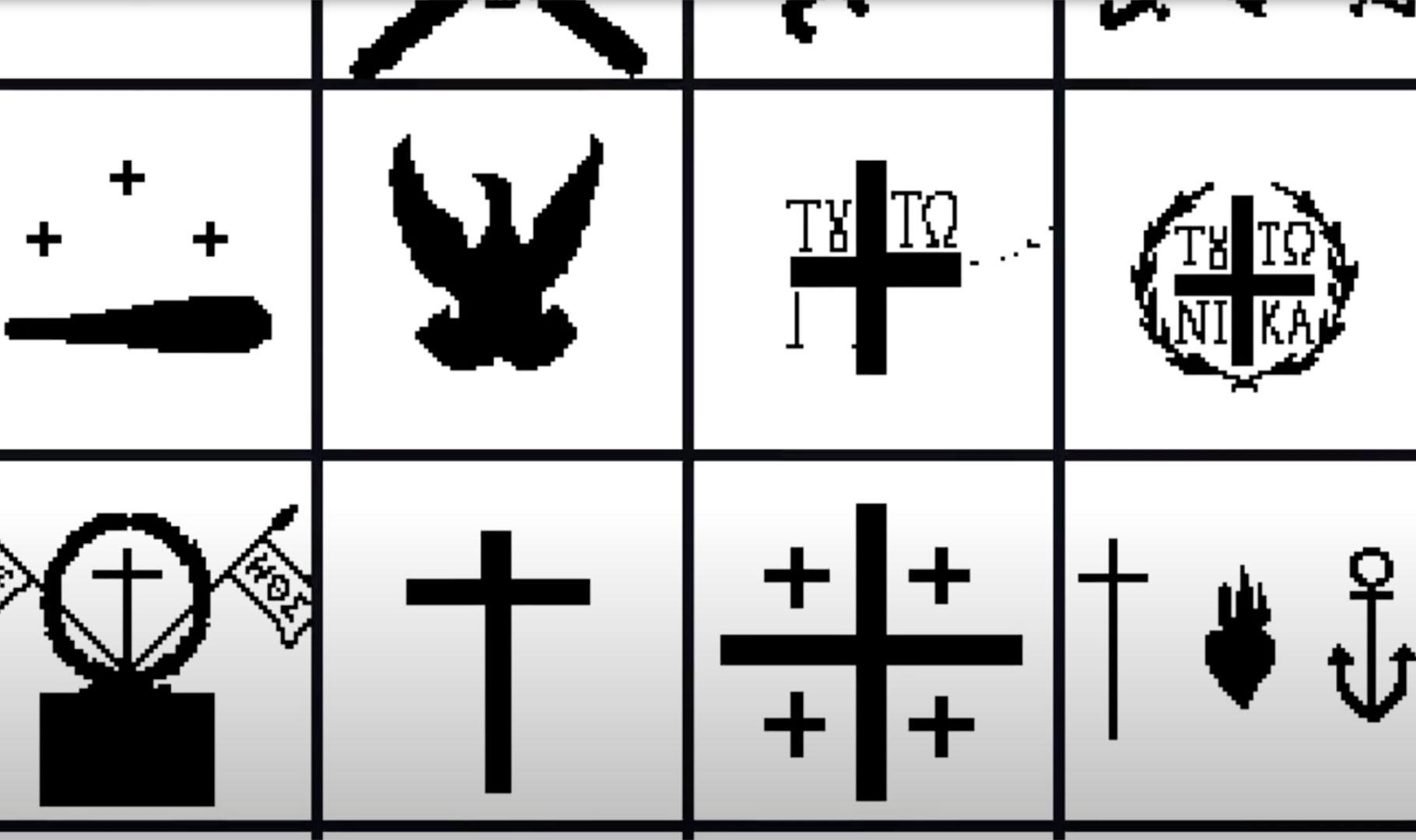

Supporting the dual meaning of the word πανίον (piece of cloth)1 in the exhibition’s title, Maria Varela “invents” another flag, the creation of which she presents in the video essay of the same name. To begin with, she gathers symbols and designs predominant in 45 different types of flag from the collection “Flags of Liberty” of the National Historical Museum, thus forming a database rich in visual elements. Each symbol is transcribed into a binary pattern on the surface of a matrix, while an algorithm defines where the common elements between the entries are on the grid. In this way, only the pixels permitted by the algorithm to participate in the “creation” of a new formation are kept, and are designated by black dots. These dots in turn constitute a new, digital motif, which owes its formation to the pre-existing, established structures and motifs supplied to the algorithm, since it is quantitatively defined and also formalistically influenced by all the preceding ones.

So, much like a skilled bricoleur – as approached by Claude Lévi-Strauss (The Savage Mind, 1962)–would do, the artist does not simply record or copy what is there, but she refers to the available material and to “whatever is at hand” and, making good use of these things, “she builds” from scratch (in the present) a motif out of the dots connected on the matrix. At the same time, the matrix produces a grid-like area, like a cross-stitch pattern, on which the motif is embroidered with golden thread. So, at a first glance “we can read” three codes, schematic but recognisable, on the embroidery: the cross, the eagle and the snake, which find their place in the new scheme.

The project however is not finished nor yet complete. With the implicit desire for a symbolic interaction between additional elements that (re)fuel the feeling of “belonging”, the artist lines the motif with a cloth made of remnants of clothes bearing an equally symbolic and ideological dimension: the “fustanela” and the “Amalia” costume, which with the creation of the new Greek state were officially judged as deserving the effort to crystallise the national consciousness of the Greeks through a common “appearance”.

The final composition reminds one of a [mnemonic] assemblage, a splicing of Objets Trouvés, only composed of the tatters of the aforementioned costumes, which were possibly made in the Lykeion ton Ellinidon Workshop. They all constitute “traces of memory”, archived for the sake of the collection, but with no one to trace them, since they are damaged and incomplete and therefore not very interesting. This emphasises the meaning given to the word “archived” in the Triantafyllidis Dictionary –something that “ceases to be an object of research, occupation or interest, that is, little by little, forgotten”.

Sewing together the remains of these garments, Varela creates –in its artistic version – a new whole (in the sense of a group of fragments and a collection of statements) from the “construction” materials of our collective identity. Worn-out bits of fustanela in which tiny rags of “Amalia” dresses are nested, come together to form εν πανίον (one piece of cloth) which also serves as an underlayer “reinforcing” the initial motif. Thus, by combining the model of the archival artist, as described by Foster, and at the same time using elements of Nicolas Bourriaud’s thoughts on the art of postproduction (Postproduction. Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, 2002), she attempts a remix of existing materials in order to create a new production, a post-production that is full of hints.

An analysis of the work and its building “techniques” was attempted above by ripping apart Varela’s πανίον (piece of cloth) into the individual pieces that composed it. In the work, the symbols change their “interface” and the charge of their message. They become part of new contexts, are not only intertwined with each other, but also mix with other elements of the collective identity in order to create a new form. Therefore, through invention– according to the term used by Hobsbawm and Ranger (The Invention of Tradition, 1983) – previous references and shapes transcend their original existence, and are transformed, mutated and, through this artistic recycling, “are preserved in a new form”, as hints or indirect references, promoting the feeling of the past’s presence in the now and creating an opportunity for new readings and meanings.

Moreover, Varela does not “reject”. She transforms, matches, composes pieces and unifies them in a whole in order to give them solid meanings, but without being carried away into a historical retrospection. She coopts the archival material–surpassing, however, what is called appropriation art and entails an ideology of ownership. She approaches the cultural reserves as a finding that can provide information from the past, and then she gives it back in a mediated form as a ”re-construction”, as a “post-production”, through which History can be read with a new dynamic.

In this case, Varela’s artistic writing and stitching is a product of Archival Art, which the artist herself cosigns together with an algorithm. This processed image of the past in the present (re)introduces our terms of “reference” and summons us to a different way of reading the discourse on identities and on the way(s) in which they are produced, reproduced and/or transmitted. At the same time she places the spotlight on insightful thoughts on collection and reflection, while also creating the right conditions for reflection on the role of archival material as a medium for original artistic creation in the place of a linear historical and narrative approach, while she situates modern creations on the “unofficial” side of preserving and achieving memory.

Varela’s πανίον (piece of cloth) was placed in the Lykeion ton Ellinidon headquarters, providing– in a symbolic way–an “invented” visual identity for the exhibition.

- 1. ἕν πανίον: a) one “piece of cloth” that, all along, every time it was wrapped, stitched or attached to the human body, turned from two-dimensional material to a three-dimensional garment and accordingly a “hallmark” for those wearing it, b) the meaning connoted by πανίον of a revolutionary flag, as a symbol of the nascent independent Greek state.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Maria Varela

Vassilis Moschas (Polygrains)

Angeliki Hadji

Nikolas Konstantinou

Yiota Argyropoulou

Penny Saccopoulou – Valtazanou

Tania Veliskou

National Historical Museum, Athens, Greece, Traditional Costume Workshop and Angelos Theodossiou and Nikos Sotiriou, as well as Zoe Kona and Ntina Leonardou