Neither, none, not, or the whimsical weaving of a myth.

With Jules Verne’s novel The Archipelago on fire as her point of reference, Aggeliki Bozou focuses on how the 1821 revolution is interpreted and reworked in fictional storytelling, searching for points both of contact and of distance between two distinct fields of writing: history and the fantastical plot of the story. However, instead of focusing on their obvious differences, she redirects her attention to the illustration of travel writing and other publications, treating the depictions as visual versions of a form of reality and imagination with eclectic affinities to the practice of adaptations in art.

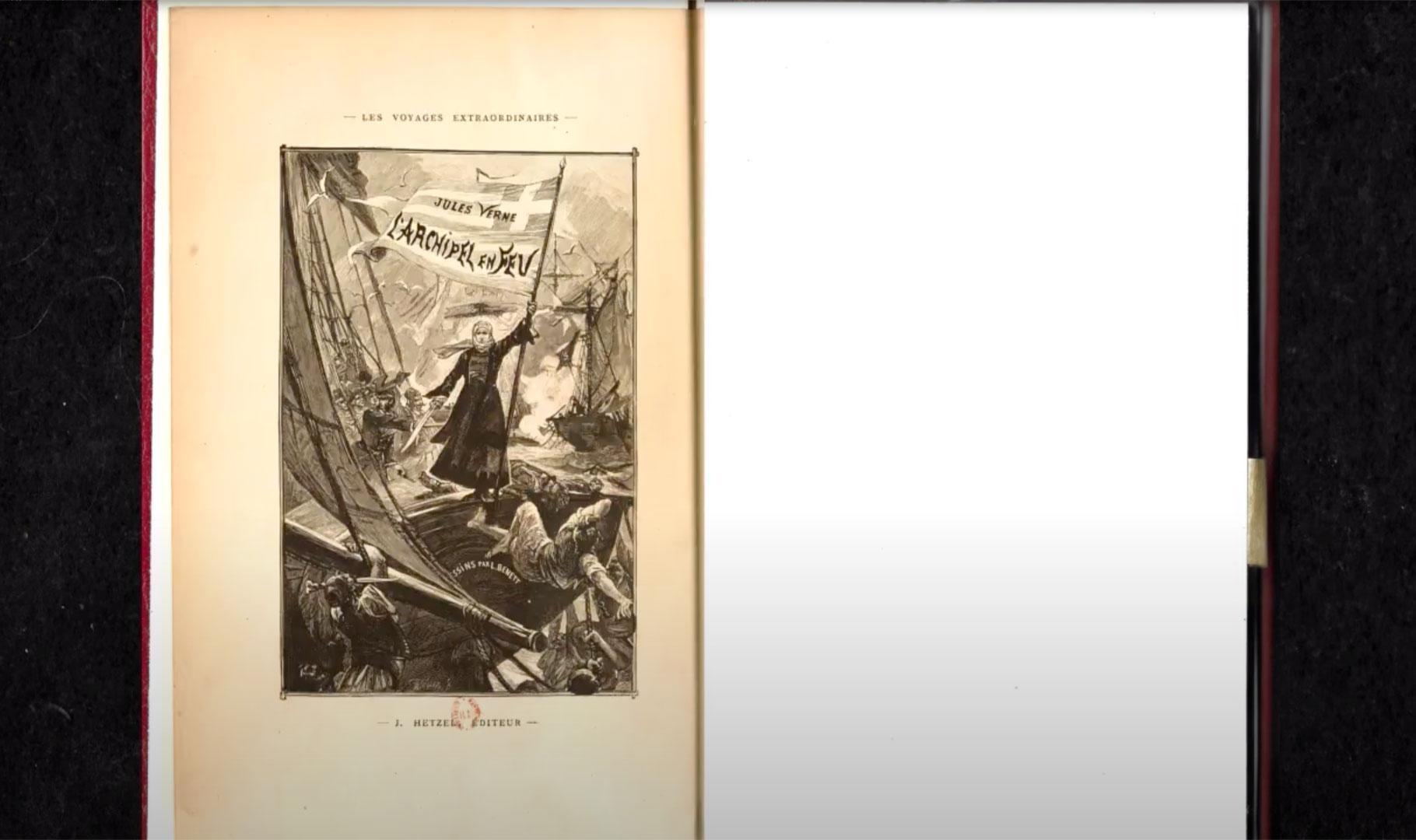

The Archipelago on fire (French title: L’ Archipel en feu) by Jules Verne is an adventure novel of entirely Greek interest, with themes around piracy in the Aegean Sea and the love between two young people. Although the novel was written in 1883, the plot is set in the time period between 18/10/1827 and 7/9/1828, and is centered around the events that took place just before the Navarino naval battle. The principal character of the book is the captain of the sailing ship Karysta Nicholas Starcos from Mani, who collaborates with the pirates infesting the Mediterranean, with the support of a banker from Corfu. Starcos was the son of the widow Androniki Starcou from Oitylo, who participated in the battles of the Greeks for Independence, and was known only by her first name, as she did not want to use the last name that her son had dishonoured, according to Verne. Other characters in the plot are also French Philhellene Henry d’ Albaret and the banker’s daughter Hadjine Elisundo.

The novel is first published as a serial in the newspaper Le Temps between June 29 and August 3, 1884, while Hetzel Editions publish it the same year with illustrations by L. Benett. Almost simultaneously it is translated into Greek by Eleni Kanellidou and published in the Athenean newspaper Kairoi (July 1884-January 1885) under the title “The Aegean in turmoil”.

In his work, Verne praises the Philhellenes’ participation in the struggle of 1821, as well as exalting the heroism of women in the character of Androniki from Mani. At the same time, nevertheless, he dares to mention issues that are usually kept quiet, like the spread of piracy in the Kakovouniotes area, as well as the practice of slavery by the pirates, who captured entire populations and took them to be sold in the slave markets of the East.

Though Verne’s primary concern was the fantastic plot of the story– as an article of the Kairoi newspaper mentions– the inhabitants of Oitylo were bothered both by how the author describes the Maniates and by his allusions to the piratical activities of their compatriot Starcos. Verne’s reply in Le Temps was a natural consequence, as was the reaction of the newspaper Kairoi.

So, in the first chapter of his novel, Verne writes about Mani and its inhabitants: “[…] At the moment that this story is written –and not at the moment it was set– the Maniates, or rather those bearing that name, remain half-barbarians, caring more for their own freedom rather than that of their country. They love to quarrel, they are vengeful and, like the Corsicans, they hand down family feuds, which are erased only by blood, they are looters by descent […].”

It is not confirmed if Verne ever made it to Greece during his travels in the Mediterranean in 1878 and in 1884. According to the writer, his knowledge derives from the work Univers pittoresque published by the Editions Didot, where –among others– Andreas Miaoulis’s past as a pirate is mentioned. Furthermore, Verne draws elements from the work by the Secretary of the French Embassy in Athens Henri Belle The Voyage in Greece, which was initially published as a series in the geography and travel magazine Le tour du monde and as an independent volume in 1881 (Belle, Henri. Trois années en Grèce, Paris, Librairie Hachette, 1881).

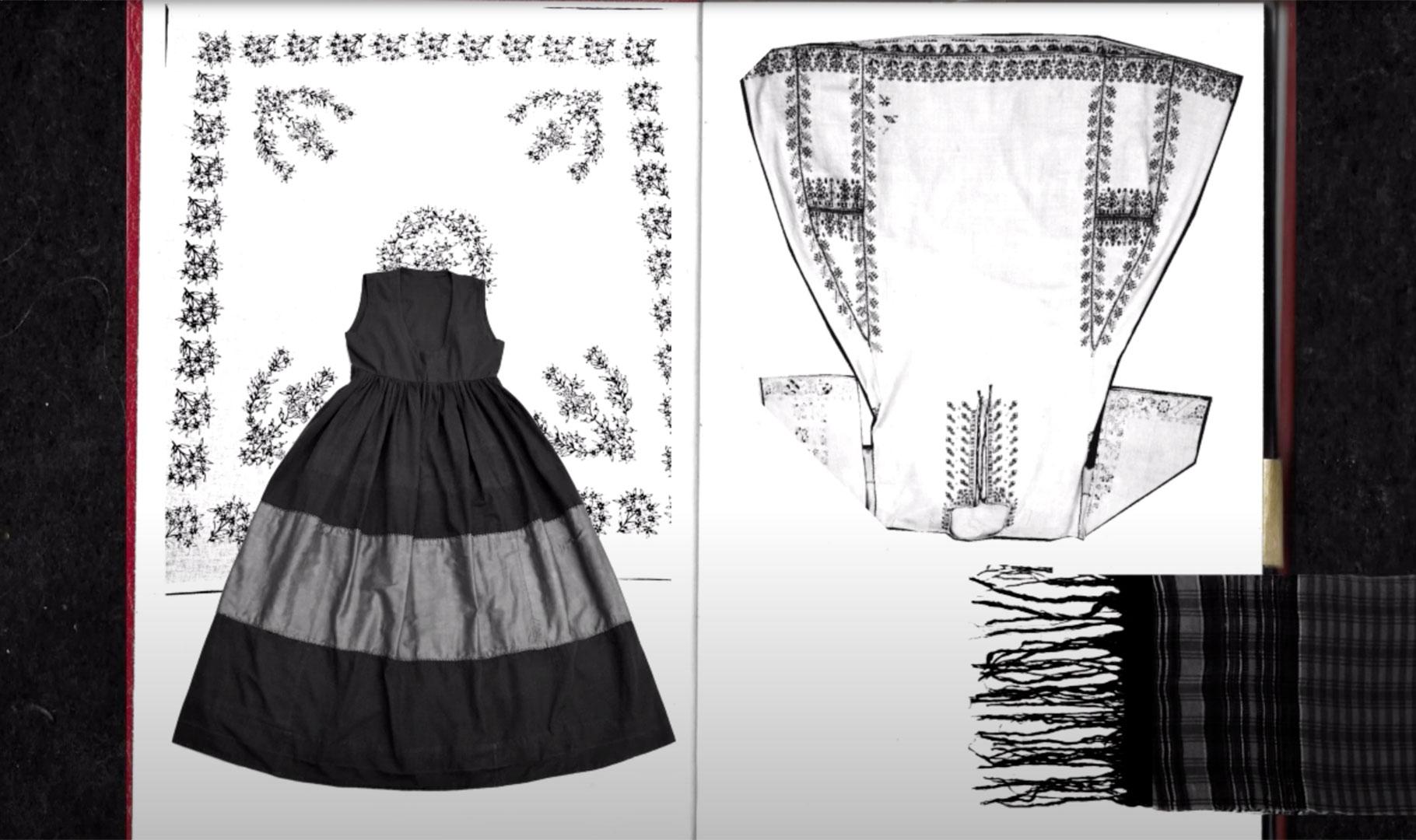

It is also interesting that L. Benett never visited Greece, either. Maybe that is why the illustrations do not correspond to the text they accompany. A typical example is the writer describing Mani’s costume worn by Androniki as “a skirt made of black cotton fabric with a narrow red hem, a short dark-coloured jacket, tight round the waist, a broad half-black cap on the head, tied with a scarf in the colours of the Greek flag.” The fact that Androniki is depicted in Benett’s lithographs mostly in the clothes of Attica’s villages with the typical foundi, a long tunic with sleeves and a wide decoration around the hem, is perhaps proof of the usual practice of many travelers and artists who made their illustrations by following their imagination or by drawing inspiration from others to fulfill the needs of publishing a travel diary.

Bozou’s work is a compilation of extracts of various of her own and others’ works, which include adaptations and transformations, whether explicitly stated as such or not. By marking up the body of the book with sketches and collage, by adding notes and attachments and crossing out parts, by changing and distorting, and by making use of the basic parts of the Mani costume, as it is defined today, the artist changes the contents of the original’s illustrated page, essentially inventing a new fictional narrative with different depictions.

Her purpose, however, is not to correct what was considered in the past to be offensive by the Maniates and to place the facts in the context of a politically correct story. Nor is her intention to play the role of the historian or of the interfering commentator. She is also not trying to propose another depiction of the depiction of what L. Benett did or did not see and illustrate. She aims at exactly the opposite. Her approach is a comment on the ambiguity of the history, on the reliability or not of the image in the works of travellers and on how history is transferred into literature – processes that embody the concepts of intermediation and of interpretation.

Recognising “fantastic reconstruction” as typical of the author’s work, Bozou proceeds to one more transformation of Verne’s work, as typically very often happens in art and especially in modern art. The transformation refers to the process during which the artist forms or recreates a theme or a picture anew, giving it new semantic charging or bringing to the surface topical or even personal concerns. Bozou expresses this reasoning by projecting, for example, contemporary versions of fire and revolution, which ignite memory on an individual or collective level. Thanos Kosmidis adopts the same practice in the soundtrack for Bozou’s work, by mixing up different musical styles and rhythms. In a similar way, the artist treats the image of Androniki as an archetype, a symbol, and an exemplar (of behavior), which could be compared to contemporary figures, thus providing different versions of what female heroism is.

Tania Veliskou studied History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, receiving scholarships from the Tsagada Legacy Fund for her performance in the programmes of Folklore and Social Anthropology. With a scholarship from the “Maria Heimariou” Foundation, she undertook postgraduate specialisation studies in Museology at the Department of Museum Studies of the University of Leicester, U.K.

She has participated in research programmes at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the documentation and management of costume collections, as well as in folklore research in situ in Northern Greece. She works as a curator at the Museum of the History of the Greek Costume of Lykeion ton Ellinidon, primarily on museological research, museography design and the curation of thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Hellenic Costume Society.

Aggeliki Bozou

Thanos Kosmidis

Tania Veliskou

Penny Saccopoulou-Valtazanou

Diana Notaroglou

Tania Veliskou